'I SEE MY FACE THERE'

- Apr 7, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Apr 15, 2022

The meaning of solidarity and what's missing in the quest to solve chronic homelessness

Under the highways and bridges of the Greater Miami area, you will find shelters molded together by the inhabitants' sheer will to survive, held up by the necessity of cooperation. The materials are the remnants salvaged after city-sanctioned clearings. If it wasn’t for the recycled cardboard, tin, and plastic in its construction, the encampment would look like homes with furnished patios full with neighbors sitting and talking. The people who live there are without housing but not without community; there are lessons to be learned from their resilience.

Lisa Jones is 50, and has been living on the streets of Downtown Miami for 18 years. Her sunburnt cheeks perk up when she notices me approaching her, a wide smile and crinkled eyes ease me. In our conversation I feel I am the first to let her speak about her life. Her voice carries the same tone of desperation I hear in all of us witnessing and experiencing Miami’s rising rents and environmental disasters. Still she’s disciplined in hoping for a better future in the same way my peers and local organizers are.

Actively experiencing substance abuse disorder, Lisa has not found the level of support she needs to maintain recovery. After going through temporary shelter programs she amounts them to nothing more than that, temporary, leaving her right back where she started. She, like other residents who live near the wharf, always finds a way to regroup in this area. These encampments offer spaces for autonomy as well as accountability with a “safety in numbers” mindset that comes from familiarity with the people and the place that those without homes have chosen to stay in.

“When we’re all together like this, we’re safe,” she says, looking around at her neighbors who she has known for years.

David Peery; an outspoken advocate and former class representative of Pottinger plaintiffs, can attest to the traumas of experiencing houselessness: during the 2008 economic crisis, with the fall of the housing market, he lost his job, fell behind on rent, was evicted, and found himself with no family and no home in Miami.

“Whenever I see someone on the streets, I see my face there… every day you’re in homelessness, it gets harder.”

He singles out intergenerational poverty and a lack of affordable housing as the causes of chronic homelessness, a systemic maintenance of poverty and extreme poverty. It’s exacerbated by the “misunderstanding in how we are all connected. How public policy excludes the poor from our economy, voting, affordable housing, and participating in the community as a whole.”

Social exclusion is the barrier to reducing societal ailments, such as homelessness, because it stonewalls potentially productive members of society. In blocking those most affected from participating, we lose an invaluable understanding and perspective of the experience, and without it, we’ll never establish a path to the solutions found in affordable, permanent housing.

“Ultimately, it’s all rooted in policymaking,” says Peery.

Public policy and the systems they uphold are human-made; they’re not immovable mountains or beyond our understanding, we have the ability to rebuild social systems so they are strong enough to uphold the rights of all.

Dr. Armen Henderson shared similar political parallels: that “when you start to draw connections like that, you start to see that the same underlying conditions that bar people from having adequate housing are the same conditions that [prove] individuals who do have housing [can be] on the brink of eviction.”

In community actions such as the Foot-Washing event, which makes pediatric care accessible to houseless locals, Dr. Henderson and the Miami Street Medicine team make wins in building bridges between those who can serve and the underserved, through education and exposure to the conditions our houseless neighbors live in. Now, Dr. Henderson and his team have founded a free urgent care, one out of only 27 free urgent care centers in Florida. He says the location at 5505 NW 7th Ave was chosen with the neighboring residents in mind.

There is a Village (Free)dge right next to the new clinic where, he says, “There are an average of 200 individuals who get food from the fridge every day.” Those experiencing food insecurity, who use the (free)dges as a resource, are overall financially insecure. Housing, physical and mental health, food; in poverty, all the basic necessities are compromised because of the lack of resources extended to those most in need.

“We aim to provide a free walk-in clinic that does not require appointment or insurance. The clinic is an extension of how I feel health care should be in this country, free and accessible.”

This awareness of how all struggles are inevitably connected is at the heart of Dr. Henderson’s efforts and the clinic's operations. He employs medical students to provide the clinic’s free services to not only “change the narrative in politics but in education.” Training students through exposure debunks the myths of homelessness and instills a compassion that not only makes them better medical professionals, but it ensures that any patient they encounter, no matter their social status, receives equal treatment.

Misinformation about the experience of being homeless compromises society’s understanding of the full extent of services needed to address the traumas that perpetuate homelessness. Unless society collectively ends the othering of homeless people, unless the people and organizations closest to the issue are part of the problem-solving process and polilcymaking, homelessness will persist.

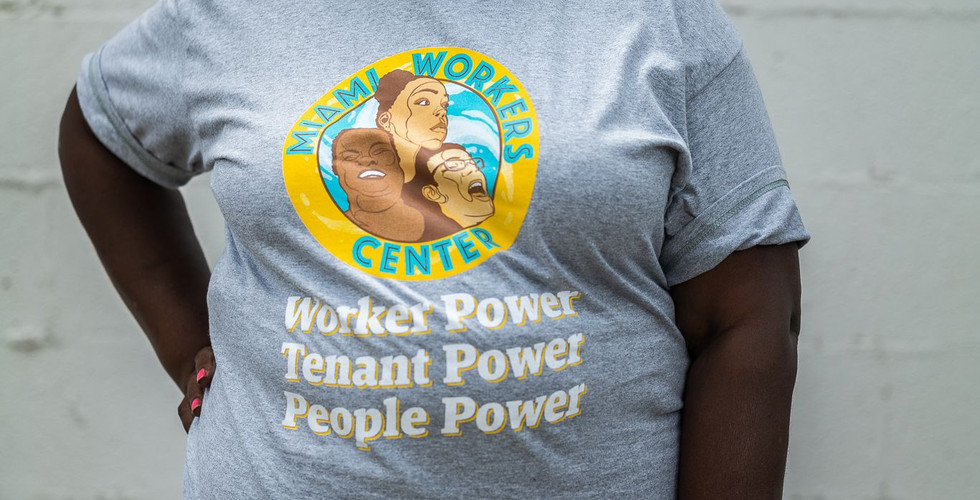

Miami Workers Center (MWC) is an organization that “works alongside people rather than over-promising any services,” as Norma Uriostegui, tenant organizer with MWC, describes it. Most, if not all, members of MWC are working-class renters who have faced evictions or abuses from slumlords. In essence, MWC practices homeless prevention through grassroots organizing.

by Greg Clark | Good Miami Project

Norma says “for us, it isn’t about rushing into crisis response, it is about what needs to be fundamentally changed in order for folks not to be pushed out of their homes so easily, as it is in Florida. We’re about doing the slow, intentional work of base-building to get to the root of the problem.”

Through teach-ins and strategy sessions where all members are invited to speak, MWC has created an informed people’s movement that challenges specific policies that historically burden renters and working class people. In less than a year of mobilizing, they won the creation of a new government resource, the Office of Tenant Advocate, where renters can go directly to file complaints and access assistance, the first of its kind in Miami-Dade. While a 60-day notice period for any rent increase is now required by law, an entire Tenant Bill of Rights –which would actualize a tenant's right to legal counsel, place a cap on application fees and other protective measures – is now being introduced to legislative bodies, sponsored by Miami-Dade commissioner Raquel Regalado.

“It’s never been a single person, or the government, having a sudden change of heart, it’s always been people pushing forward,” says Norma, and through MWC’s organizing efforts, we can see the change in both policy and people.

Educating vulnerable communities on their right to freedom and security yields the power of choice. This is what differentiates the Miami Workers Center from other organizations. MWC's vision is centered on the idea that everyone has the same right to demand their freedom and security.

Solidarity is about unity; it grounds all peoples in our connected struggles, and finding strength to overcome those struggles defines the power of community. But the practice of solidarity is not exclusive to political action; rather, it requires the reshaping of societal and material dynamics that then inform changes in policy.

Carlos Banks, creator of Clypr, is using his business to promote volunteerism within his community of barbers. For three months, Carlos gave free haircuts to residents of Camillus House. To him, “it was a no-brainer” to collaborate and provide his community with what he could. He explains how in a small business model, you “are part of the community, and without community, we can’t be successful.”

Miami-Dade County Public Schools runs Project UP-START, a program that helps students in unstable housing conditions succeed in school. In collaboration with the Homeless Trust, Project UP-START created an online Homeless Sensitivity and Awareness curriculum for elementary and secondary schools. In person, UP-START volunteers are always available to meet at The Shop located at 750 NW 20th street. Here, Miami-Dade County’s homeless students and families in need can “shop” for food, clothing, shoes, and personal items all-new, all for free.

The key to making a difference is finding niche ways to redistribute resources and revitalize our connectivity to one another. Identify the talents you have at your disposal and partner with others who share a common mission. A Small Hand (ASH), is a group of Miami locals who go out on Fridays to distribute clothes and food to the people of Overtown; they are solely funded by donations and collaboration with similar groups, sharing information and materials.

Daniela Hernandez, co-founder of ASH shares, “My hope and perseverance grows when we are able to effectively collaborate with other groups who share the same heart we do for this cause. It takes a lot of effort to do this work alone, and when we are able to work together, it reminds us how easy it can be [to share resources] and that other people are dedicated to making a difference in this community as well. It shows the world that a greater difference can be made when we work as a collective.”

Since their first year of service, ASH has made close connections not only with other organizations but with the people they support. Daniela says “our philosophy is simply to ensure the members of our community who have been displaced and are experiencing houselessness feel a sense of consistent support and friendship from us.”

During a food distribution, ASH introduced me to Ernst, 70. Living under a bridge on NW 3rd avenue, his favorite saying goes “today is the tomorrow you looked for yesterday.” There is no greater time than now to join an organization, volunteer for a food distribution, or push your local politicians to act with compassion. When the government, service providers, and members of the community can sit at the same table and when the narrative of who homeless people are is ruled by those experiencing it, we will see a more just world, and progress may finally be for all.